For all the roles Colman Domingo has taken on in his 33-year acting career, there’s one that still eludes him: Feste, the royal jester in Shakespeare’s “Twelfth Night.”

“Shakespeare’s clowns are some of my favorite roles to play because they are the philosophers,” the actor says. “They are the eyes, the ones who can really critique. And they usually have a very interesting sense of humor because they’re very in tune with humanity.”

When he was growing up in Philadelphia, Domingo considered himself to be a keen observer of people. He describes himself back then as a “bona fide nerd”—someone who was better at watching than being watched.

While he was studying journalism at Temple University, his mother encouraged him to take an elective, just for fun. He remembered enjoying a summer theater program he’d done when he was 12, so he decided to register for an acting class. When his instructor told him he had a gift, he began to consider performing as a possible career path.

Then, friends of his moved to San Francisco and invited the 20-year-old Domingo to stay with them; he accepted their invitation. “I was like, let me go…for a semester and just be, live. And I can always go back to school,” the actor recalls. “I stayed there for 10 years, and I never went back to school.”

In an attempt to catch up on the formal training he felt he was lacking, he took more acting classes and read books on the craft, including Uta Hagen’s “Respect for Acting.” “I had questions about everything: Why is [the scene] set that way? Why are we doing it like that?” he says. “I was developing a writer’s brain and a dramaturgical brain.”

The energy of the ’90s San Francisco theater scene helped him feel comfortable sharing his opinions and exploring topics beyond his expertise. This is when he developed the skills that turned him into the multihyphenate he is today.

Domingo is known for taking on prominent film and television roles: a clever con man on AMC’s “Fear the Walking Dead” (2015); a dedicated father in Barry Jenkins’ film adaptation of James Baldwin’s “If Beale Street Could Talk” (2018); and a recovering drug addict on HBO’s “Euphoria” (2019), which earned him an Emmy. But the actor got his start in theater, performing and directing in San Francisco and both off and on Broadway. He’s also written for the stage, including a one-man show based on his life called “A Boy and His Soul,” which debuted in 2005 at San Francisco’s Thick Description.

Domingo credits his time in the Bay Area with kicking off his career. “I went there to become an actor, and I left an artist,” he says. In those early years, endless auditioning led to a gig with Make*a*Circus, a company that toured California, and later to roles in Shakespeare productions.

“When acting’s done well, you’re connected to every character that you play. You have questions about that character, and then you want to fight for them. You want to be their advocate.”

“I’m so grateful that I had Shakespeare as a base for most of the things that I do, because if you can dust off a 300-year-old joke and make it work, that’s pretty dope,” he says. That’s why he’s so drawn to Feste and the Bard’s other clowns: They aren’t just telling timeless jokes—they’re asking probing questions.

There’s a direct connection between these philosophical jokesters and Bayard Rustin, the real-life civil rights activist Domingo plays in “Rustin.” The biopic, directed by George C. Wolfe and written by Julian Breece and Dustin Lance Black, focuses on the period when Rustin was organizing the 1963 March on Washington, which culminated in Dr. Martin Luther King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech. The film colors in the details of a man who has been largely forgotten by history due to the fact that he was openly gay. Similar to Feste, Domingo’s Rustin is witty and always ready to verbally spar. But he leads with his heart, challenging the civil rights leaders of the ’60s with a question that still resonates today: What’s the point of freedom if it isn’t for everybody?

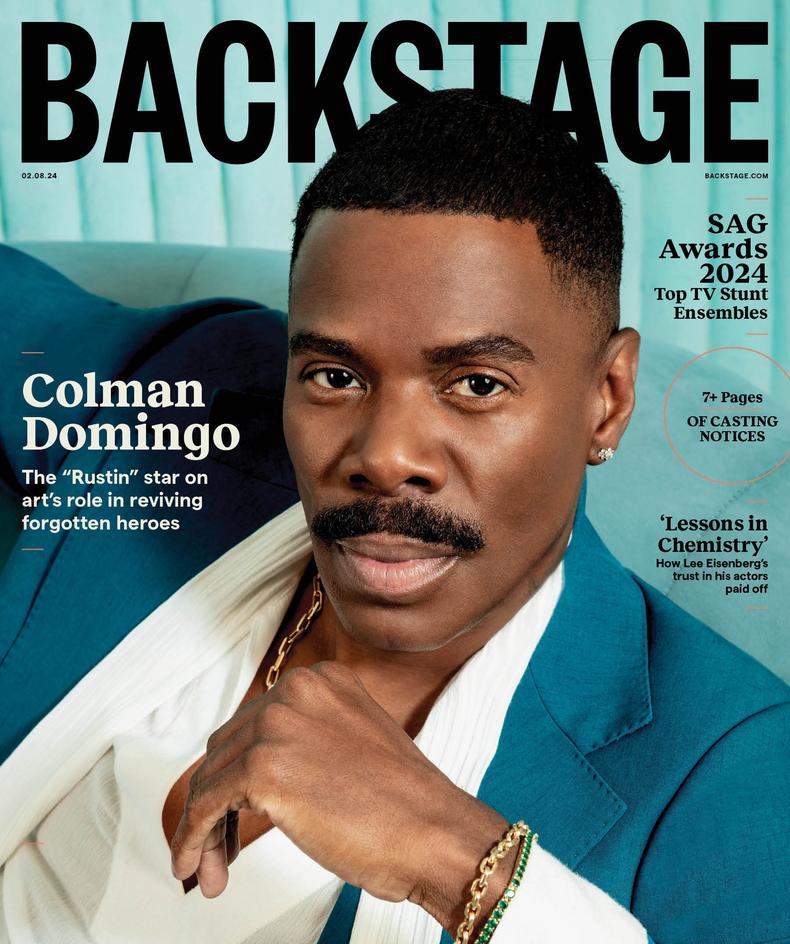

Domingo’s spirited portrayal has earned him several accolades, including first-time nods from the Golden Globes, the BAFTAs, and the Academy Awards. He’s the first Afro Latino performer ever to be nominated for a best actor Oscar, and only the second openly gay man to be recognized for playing a gay character in the category.

What drew you to the role of Rustin? What made you say, “I want this”?

There’s something about him that I understand. He was someone who was truly, in every sense of the word…an outlier. From the way he was raised: a Black man in America, raised Quaker in 1963…who [had] liberated himself enough to have an interest in playing the lute, an old Elizabethan instrument, and [singing] Elizabethan love songs and hymns. [He] also was such an Anglophile that he would give himself a very unique mid-Atlantic standard accent.

He wasn’t—and this is what someone who loves him said—an easy man; he wasn’t easy to figure out. And for me, I’m drawn to characters like that. What makes him tick? How did he come to be? And then to have that much confidence and that much swagger and that much undaunted spirit at that time? I’m very curious about him. I’m very curious about people because I always want to know their story, because maybe I’m trying to find how we relate.

I think when acting’s done well, you’re connected to every character that you play. You have questions about that character, and then you want to fight for them. You want to be their advocate. And that’s what I feel; I wanted to be [Bayard’s] advocate in many ways.

How did you balance capturing a historical figure with bringing your own interpretation and understanding to the role?

Early on, I had to make a decision of…when I could involve people who knew and loved [Bayard]—because for me, there was a balance. I’m playing a real, live human being who affected lots of people; and there are people alive who knew and loved him. But I’m making a film, not a documentary. So I had to do my work and due diligence as an actor…do my research and respect the work and respect the building of this person.

But I have to make decisions that are for dramatic license as well, like whether I want to bring his voice down. He had a very high-pitched voice, and I wanted to bring it down so it’s more sustainable to the ear and people can follow that and not be distracted by it or think it’s mimicry. I had to find the essence of it. I had to…make choices [about] how he existed in spaces where he felt like he was not wanted versus spaces where he felt liberated. So I had to make all these decisions.

“Films like ['Rustin'] are not just made for Black people. They’re made for anyone who’s curious.”

Which people did you speak with who knew Rustin?

There are two people who I’ve become very close with. One is [civil rights activist] Rachelle Horowitz, who was also featured in the film. And she’s just a joy. She’s become sort of a mama to me, even [in] the way we relate with texts and phone calls. I do feel that it’s like, in some strange alchemy [or] spiritual way, I’m sort of standing as a representation of someone that she loved and had a great relationship with. I know that [we were] fulfilling this for each other in some way. We’re linking to the past in some way, but we’re absolutely living in the future.

And then there’s Walter Naegle, who was Bayard’s partner until his passing. He is the keeper of Bayard’s extraordinary legacy. There [are] religious [sculptures] that Bayard collected from around the world in their house; there [are] beautiful prints and photography, books, and walking sticks. He was a collector; he collected many things; he collected jewelry and necklaces.

It was a rainy day in New York, and [Walter] pulled out some jewelry and he said, “I believe Bayard will want you to wear something of his.” And he said, “Please, just choose. Let the energy be drawn to you.” And I chose two rings. I said, “Is it OK if I have two?”—because two were calling out to me, and they fit me beautifully. And he [said], “Wear it lovingly.” And I do.

How do films like “Rustin” fill in the major blanks of our collective memory? How does this movie expand the legacy of someone who was important to the civil rights movement but whose role is often overlooked?

I’m going to quote a colleague of mine, Rhodessa Jones. When I was a young actor in San Francisco, she left us with some words after a reading. She [said], “Politics does not work. Religion is too eclectic. But art—art might be the parachute that saves us all.” And [I] remember the words: “Art might be the parachute that saves us all.” There’s a question—because when we’re being lied to about history, when books are being banned, when people are feeling like they have no access or voice, we go to art. Art does change lives, which is why we know that the first program to go in any high school is an arts program. These are the lifelines to know who we are. It’s joyously defiant; that’s what art is.

Imagine a 19-year-old seeing “Rustin” and thinking, Remember [when] Audra McDonald played Ella Baker? Ella Baker was only in a couple scenes. What was her story? Let’s find out about Ella Baker now. Let’s find out about A. Philip Randolph [played by Glynn Turman]. And that’ll lead you to Diane Nash. It’ll lead you to Andrew Young. It’ll lead you to all these places to have more of a sense of who we are.

That’s how I found out about Bayard Rustin when I was 19 years old at Temple University—[but] not in a classroom. This was through joining the African American Student Union…to seek out more knowledge about myself and my place in history. Bayard Rustin came up in a conversation: “He was this, that, and the other, and he organized the March on Washington. And pretty much, he’s been marginalized in history books because he’s openly gay.” What? It really makes you rethink, reframe….

So I do think it’s a great tool, having films like this. I always want to remind people of this: Films like this are not just made for Black people; they’re made for anyone who’s curious.

Because this is white history also. This is American history.

Absolutely. That’s why even the idea of Black history and how it has to be a specialized course—we understand why that had to happen, because it wasn’t being taught. But white folks need to learn Black history, too, because this is American history. We need to learn a collective history.

I think that’s why things are being so challenged. Why are people challenged with history? Because it makes them feel bad. And I think [that’s] OK, because there are some messed-up things that have happened, and the only way to get better is for us to know that messed-up things happened.

The film captures a challenge Rustin was dealing with in his time—one I think is still an aspect of social movements now—which is that people are expected to compartmentalize their identities to serve the greater good.

The intersectionality of [Rustin] being Black and queer—yes, that was so important. We don’t usually see that. Most films will take the queer out of it in some way, or really make it just a light footnote. And I love that we go deep [into] it. You need to know how he was trying to make a life for himself [and have] relationships, and how tricky that was. And you know that there were no models of the relationships you [could] have. He lived in dark spaces while trying to do the work of civil rights in the light.

The intersectionality of [Rustin] being Black and queer—yes, that was so important. We don’t usually see that. Most films will take the queer out of it in some way, or really make it just a light footnote. And I love that we go deep [into] it. You need to know how he was trying to make a life for himself [and have] relationships, and how tricky that was. And you know that there were no models of the relationships you [could] have. He lived in dark spaces while trying to do the work of civil rights in the light.

Do you have any advice for someone who’s just starting out in acting?

I always want to tell people that it takes a sense of not only dedication, but being clear about your purpose, your intention. There’s a bit of a mindfulness that you need to adapt in this industry that will help you build a healthy, creative life where you feel like you have purpose. Success is based on where you find success. I felt successful the first time I was doing theater for young audiences. And then I started moving into more regional theater. And that’s still a part of me. I love creating communities and expanding….

I think you just have to be dedicated to the life of an artist and actually find places where you will thrive, not just get work. “Oh, I should move to L.A. or New York.” No—go to where you think you can find out who you are as an artist first. Go to Portland, go to Chicago, go to San Francisco. Why throw yourself into this great big sea when you don’t even know who you are as an artist? Go where you’re going to fall in love, where you’re going to experience something, where you’re going to learn about other things that are just as important. That’s the key to it: being curious not only about people, not just about the process or acting; you’ve got to be curious about living.

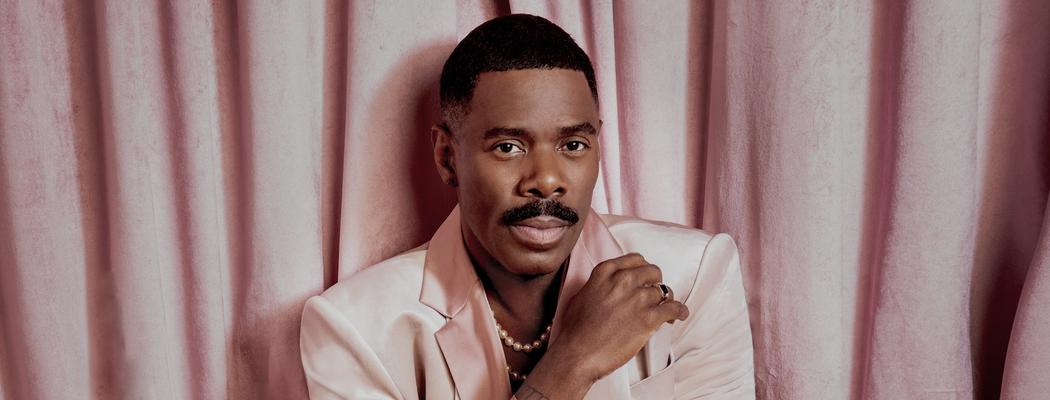

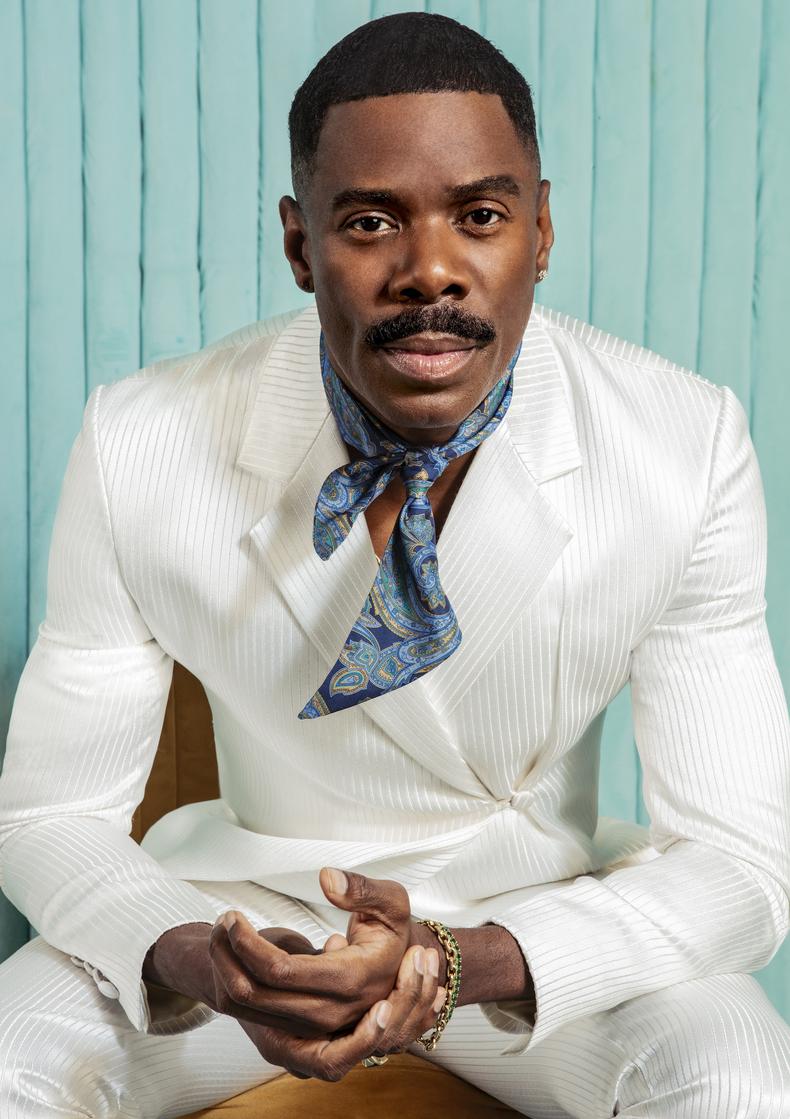

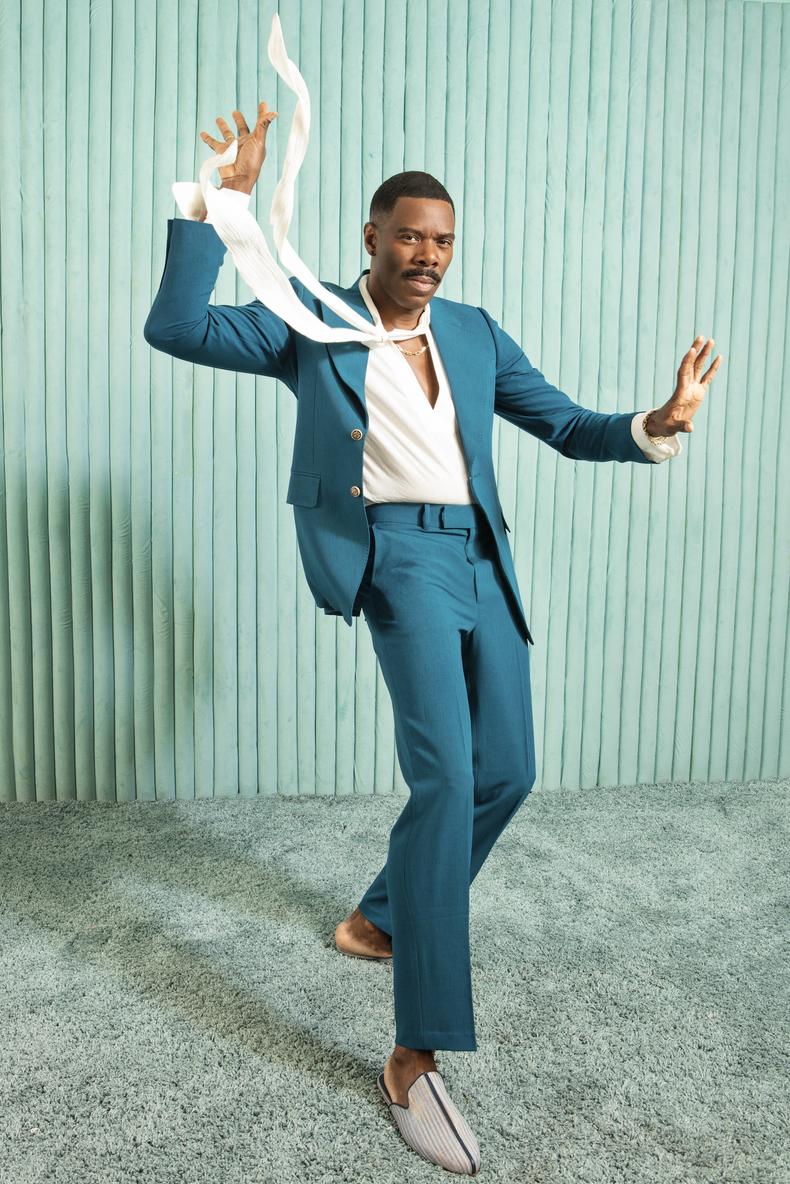

This story originally appeared in the Feb. 8 issue of Backstage Magazine.

Photographed by Roger Erickson on 1/22 in L.A. Styled by Oretta Corbelli. Groomed by Amber Amos. First look: Suit by Dzojchen, shoes by Scarosso, neck tie by Viggo London. Second look: Suit and shirt by Dzojchen, boots by Warren Alfie Baker. Third look: Suit and shirt by Dzojchen, shoes by Ifsthetic. Cover designed by Ian Robinson.