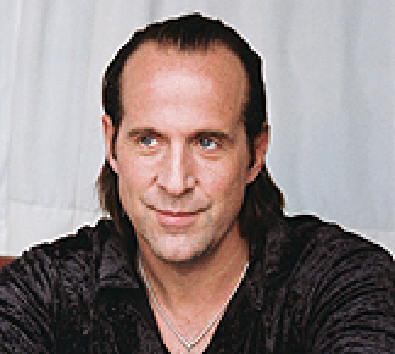

It's intended as a compliment to say I was a little scared of Peter Stormare. It's a testament to the actor who has so memorably played a variety of nasty characters in films such as Fargo, 8mm, and Minority Report that my first instinct upon meeting him is to warn him that people know where I am, and, if anything were to happen, I would be missed. But within moments, it becomes clear that the self-proclaimed "normal guy" is just that, when he starts playing air guitar and treating us to songs from his band's upcoming CD. And if there were any doubt, just consider said band's name, which hints at his self-effacing humor: Blond from Fargo, in tribute to Stormare's breakthrough American film role as a sleepy-eyed killer in the deliciously twisted Coen brothers flick.

There are a few things about Stormare that might come as a surprise, not the least being that he lists Family Feud among his favorite TV shows. For an actor who has made such an impression on film portraying monosyllabic brutes, he has played everything from Hamlet to Rasputin on the stage. In his native Sweden, he worked closely with the legendary Ingmar Bergman for many years, appearing under his direction in plays such as Miss Julie and King Lear. As a director, Stormare has helmed projects at New York City Opera, the Royal National Theatre of Sweden, and the Globe Theatre in Tokyo, where he served as the associate artistic director. He is hoping to make his feature-directing debut in the near future, and his dream is to eventually direct "strange movies with fragmented stories and poetry where you can just lean back and doze off if you want to and transcend into another dimension."

If this persona sounds like a contrast to the delightfully evil roles audiences are accustomed to seeing Stormare in, it's important to remember that he's just as good at playing nice. His performance as a sweetly devoted would-be suitor in Lars von Trier's Dancer in the Dark provided the film with some of its most human and gut-wrenching moments, and his powerful work in last year's Birth was the heart of a complex story. In Sweden he played the title role of a James Bond–style agent in the series Hamilton, a massive hit that proved his mettle as a leading man. He's also showcased his humor in more mainstream roles, such as his turn as "Slippery Pete" on a classic episode of Seinfeld or his goofy Russian astronaut in Armageddon.

In the Keanu Reeves–headlined Constantine, opening this week, Stormare gets to combine elements of that wicked humor with pure menace, playing perhaps the biggest villain of his career: The Prince of Darkness. It's a small but pivotal role in the supernatural thriller, and his fey, prancing devil all but walks away with the film with only a few minutes of screen time. Back Stage West sat down with the actor at The Bungalow Club in West Hollywood, where he sometimes performs with his band, to discuss theatre, directing techniques, and how good it can be to play so bad.

Back Stage West: How did the role in Constantine come about, and is it flattering to be thought of when casting Satan?

Peter Stormare: I think they were looking at a lot of people and different angles and aspects. I don't really know the backstory, but I think they asked Jack Nicholson, actually. But it's a tricky thing. It's a first-time director, it's a potential franchise, and what do you do if you get somebody like Jack Nicholson or Clint Eastwood, some really big name who comes in the last 10 minutes? There are two [possible results]: It can elevate the movie, or it can take away from the movie completely. If you have an icon, it can take a movie in a whole other direction. I think they looked at a lot of scenarios, and in the end they settled for a lesser-known face. So when I make my entrance, I am the devil; I'm not personified by my face. I think it turned out good; I'm there as the character. You know, American movies, people are not always playing parts: They're often playing what they are as a person. Here, I could be a character. I think it was a good solution to use a lesser-known guy. I know [director] Francis [Lawrence] kept saying I could do it, but others were holding out for a bigger name. The smarter people knew it was tricky, though, so finally they agreed, "Let's hire the crazy guy and see what he can do with it."

BSW: Did you have a lot of input in the character, adding some of that flamboyance and humor?

Stormare: I always add. It can be horrible to play bad guys, but I try to bring in an element of something that makes people smile at the same time. They want to come closer to the character. If you're just gross and ugly, people back away in the seats and don't want to look at you. Even as a menacing killer, I would try to portray him with a little charm to bring the audience toward me. And that's hard, that's the hardest part, I think, in acting, to really play a bad personality and give him a little bit of charm or depth, or just something to intrigue the audience. You see it too many times--people who are playing bad boys--they become very one-dimensional. They just come in and scream and are ugly and in your face all the time. That's the easy way to attack a part. It's harder to sit down and say, "How do we do this so people are drawn to him?" And I always think it's more intriguing to do it in a way where the audience is entertained.

The less the audience is distracted by clothes or horns or hooves and strange oddities, the more they can see the character. It's an old theatrical trick. If you don't carry too much garbage with you onstage, they have to concentrate and listen to what you're saying. It's an old theatre rule I learned from the beginning.

BSW: Having played so many bad guys so memorably, did you ever worry about being typecast?

Stormare: Well, I always say I don't mind typecasting. I grew up onstage, and the most boring thing to do onstage was Prince Valiant or the good, clean guy. Onstage you always wanted to do the crazy characters, the guys who had committed a crime or were on the outskirts of the law. Even antique dramas up to Shakespeare, there are characters you never want to do, because they're so good and clean-cut. I remember when I played for Ingmar Bergman one of the coolest parts in King Lear. If you don't play Lear, who's around 70, there are a couple of great other roles. There's one, the Duke of Cornwall, who's just the meanest.... He and his wife kill each other when they have sex. They gouge out the eyes of another character, and they eat babies for breakfast, they are so dark and Gothic. It was so great to do a part like that. There was no other part for me, even if it was bigger; this was the part I wanted. Also, you're not onstage the whole time, so you get to rest half an hour here and there.

Every actor's been typecast. And it's been part of Hollywood to promote your own face, that's why I've tried to stay in...I wouldn't call it the second division, but I like to be a passer, if I can talk hockey or football terms. I like to be not the guy who scores the touchdown, but the guy who passes to the quarterback. I have the ability and freedom to change my looks all the time where somebody like Keanu or Nicolas Cage--people I know and respect--cannot. Johnny Depp is the one who's been fighting hardest, trying to change a look. And he's been awesome at it, and that's why I admire him so much. He's backed out of projects because he doesn't just want to be the pretty guy. It's very, very hard in this system. If Brad Pitt wanted to get big and fat and put on a beard and play a comedian committing suicide, no one's going to give him money. They want him like Brad Pitt. It's a very hard situation. They can buy all the houses they want, but they don't have the freedom I have. I'm very happy in my situation, because for my next part I could shave my head and have a long beard and walk with a limp if I want to.

BSW: Do you ever wish you could play a leading role in the vein of Hamilton here in America?

Stormare: No, not really. I wouldn't mind being in a heavy drama, but people here are always afraid if I can do a perfect American accent. I was asked if I could the other day, and I said no. But neither could Arnold Schwarzenegger. These producers just the other day, they said, "Can you do a perfect American accent?" I said, "I can do a mid-American, transatlantic accent. But if you're worried about my accent, I'm worried about you doing this movie. If you have those worries, then the movie's not going to be a good movie. If a movie's driving forward and has great characters, great people in the parts.... If you think I, as an audience member, am going to say, 'I wonder if that guy's from Des Moines'--nobody thinks that way if it's a good movie." I said, "If that is your main concern with me as an actor, that main concern is a little, little thing that will grow into something big in your heart, and I would rather step out. But your movie is already shaky."

In the past, Hollywood would always throw a line in: "Oh, my parents come from Switzerland," or whatever if it was Ingrid Bergman or something. A lot of French people come here and do movies, and it's never addressed. The whole world comes together in the U.S., all kinds of accents, and audiences don't care. Directors don't care, either. It's the producers who worry about it.

BSW: Going back to the beginning, how did you know you wanted to be an actor?

Stormare: There was nothing else to do in my home village than to just bail out. I come from a place [with a population of], like, 1,000 people. In college, I was only 16, I moved about 20 minutes away and lived alone and took care of myself. I saw all my friends around me get married when they were 18 or 19. That's the typical countryside life: You get married to your high school fiancee, and you move into a little house or apartment, and you all get the same car and a microwave. I suddenly felt, around 18 or 19, [that] my life was ending. I loved poetry and rock 'n' roll and John Lennon and Jimi Hendrix. I guess I was a dreamer from the beginning. And when everybody started to get married and life was sort of over, I just started walking and continued to walk. I walked down to Stockholm, more or less. I started to study film, the history of film, on the university level. I'd never heard of Citizen Kane or Orson Welles in my life. The only person I knew from the U.S. was Clint Eastwood, and if you said Clint Eastwood in this posh class, everyone looked at you, like, "What the hell?" Everyone they talked about, I had never heard of. I had to see two or three movies a day at one point, until I collapsed after a couple of weeks.

By coincidence, I had just gotten a ticket to see theatre. I was, like, 20 years old and had never seen theatre in my entire life. It was the National Stage of Stockholm, called the Royal Dramatic Theatre. It was a fantastic show; it was cancelled after six performances, one of the biggest disasters ever. But, for me, it was like coming home. It was a divine experience; it was like being saved again, born again. I was sitting there, and the whole house was illuminated and reverberating with my power of gratefulness that God had finally led me in the right direction. It was like coming to heaven.

From that day, I started to work and aimed to get into the Royal School; it's like the RADA of Sweden. I started to work backstage at the National Theatre, and, finally, after a couple of years, I got into drama school. I continued to work at the National on weekends and nights when I was off from school. Then, after three years at the drama school, I got a job at the National. I was only 25 then and got a really good part, like a lead, in a very experimental drama about six teenagers. It was a huge success that ran for three years.

That's when Bergman came and saw me. The horrible thing was, I had a monologue where I was standing on a teacher's desk in a classroom, screaming my lungs out for 12 or 15 minutes, just racial slurs and punk nonsense. We knew he was in the auditorium. In the intermission, we were all sitting in our little greenroom, and the stage manager came out and said, "Bergman left." We were so upset. I knew he hates people screaming, so I blamed myself. But then I met him a couple of months later, and he wanted me for the Duke of Cornwall in King Lear. I was so intrigued by him, and we connected immediately, and I said, "You saw this play I was in, and you left during intermission. Everybody knew." And he said, "Yeah, I know, everybody knows when I leave. But I just came to see you, and I saw what I had to see. You were brilliant. The rest was shit, but I saw what I had to see." So we started a long collaboration that lasted for 12 years.

BSW: Having worked with so many varied directors and having directed so much yourself, what do you think makes a good director?

Stormare: To take one example of somebody people have a lot of bad things to say about, there's Michael Bay. I've been with him in two movies. He's screamed at me, yelled at me, but it's okay. Bergman did the same thing in a way sometimes. There's too much pussyfooting in this business. Directors think that psychology is the way to unlock an actor's ability to create a character, and that's pure bullshit. I don't know where it comes from. Michael Bay doesn't use psychology at all. It's very simple: Acting is very simple; it's like being a magician. Sometimes the director just has to say, "I can see the dove you're holding, hide it better. Hide it under your arm for this shot. Just take it down." It's not, like, "Hey, listen to me. To hide that dove is.... Say, do you have kids?" Michael is very direct. I just worked with Brett Ratner, who had the same thing. It's a directness that some actors really dislike. But, as an actor, I just want to hear: "Faster, slower, look left, look right." I can have ideas and suggestions, but directors already have the movie done in their brains. So sometimes a suggestion can be welcome, but if you don't do what they need in the shot, they have to tell you. And why walk around the block a couple of times with their arm around you?

I like that directness. And I think American actors are more vulnerable than European actors. I've seen people burst into tears and get angry because they think, "I'm an actor, you can't talk to me like that."

BSW: Are actors just not as fragile in Europe?

Stormare: No, it's so much faster; we have to get a result. We don't have the time to waste. We shoot movies so much faster and do theatre so fast. You don't have as much time to talk about things, like which shoes look good. I told Michael Bay from the beginning [that] I loved being directed by him. It was so simple and direct and easy to follow. And if you ask most people, they would work with him again. Spielberg is also very fast. And so enthusiastic, like a little kid on-set. That's the atmosphere a good director provides, being an enthusiastic soul.

One of the first pieces I did with Ingmar Bergman was Miss Julie with Lena Olin. We had our first run-through after one week; Bergman works very fast. Halfway into it, Ingmar says, "Stop. Peter, come over here. What are you doing? It's strange. Are you doing something very, very artistic, or is it only me that's kind of lost?" I said, "I don't know." He said, "Well, you sound like you're an actor from the 1940s, and you're exaggerating everything. Is that some sort of artistic thing, because I don't understand it. You sound really, really stupid. I wish I had a tape recorder so you could hear; it's really, really bad. Can we start from the beginning; you don't have to be so darn pretentious." I started to laugh, and I said, "Did I really sound that bad?" The other actors were laughing. Lena was making fun of me, and he says to her, "Hey, you weren't much better. Just run through the play, guys." Michael's a cousin to that approach. He'll say, "We're not doing Chekhov; it's an action movie."

BSW: Probably your big breakout screen role in the United States was Fargo. Is it true you were originally approached by the Coen brothers to do Miller's Crossing and had to turn it down?

Stormare: Yeah. Around 1989, I'd just [arrived] in the U.S. I'd done Hamlet at the Brooklyn Academy, and a lot of famous people were there, including Ethan Coen. I had a chance to meet the Coen brothers. They said, "We're going to do a movie; we thought maybe you could be in it." I went back to Sweden to continue to work and, half a year later, I get the Miller's Crossing script. There was a character called The Swede, a sniper; it was a cool part. But they wouldn't give me a sabbatical. The boss of the theatre said no. I said, "Can you give me three weeks, just three weeks?" He said, "Absolutely not." I shed tears over it. Then, in the spring, came another offer from Wim Wenders; he wanted to do a road movie in Europe with Lena and me. I also couldn't do it; I was engaged at the theatre. So, around 1990, I got an offer to do Rasputin in New York, and I went over to do it and sort of never returned. I had to return to do some things so they couldn't sue me for breaking my contract. But it was my way out. I got hooked up with ICM and my agents, they just came to me. It was a dream. I'd done Hamlet onstage, and then Rasputin was a fair success, so they just sort of came to me. That got me in with Sam Cohen at ICM. I had to go back and forth for a while, but by 1994 I moved to New York full time.

In 1995 I was working with [Joel Coen's wife] Frances McDormand at the Public in a play called The Swan, in which I was completely nude and shaved except for this long, bleached-blond hair. She takes care of a dying swan, and one night the swan comes up, and it's me. She takes care of me and cleans me up. It was a cool, strange play. Of course the Coens came and saw it, and shortly thereafter they said they wanted me to do this part. And they wanted me to keep the bleached hair. That's where they saw it, and [they] thought it worked on me.

BSW: Do you ever miss the theatre?

Stormare: Not really. I've worked with the best and done so much of it. Of course I have a craving sometimes, but I'm enjoying making movies right now. And it's hard, because I'm so anal and disciplined. After every performance, I would be banging my head into a wall and saying, "You were shit today." I could never really enjoy the performance. I loved to rehearse, but I couldn't enjoy the live audience. I didn't like what I did onstage afterwards. I was always so negative, telling myself I could have done better. Then I would wake up in the morning and spend the whole day in pain and tired, thinking about the performance coming up. It's a strange way of life. But so rewarding for your soul and your brain. You learn something new every day.

I tell people all the time, "Go and be in front of a live audience," because that's the hardest thing. If you can conquer that, you can conquer the camera. It may not pay much, but it's a craft that is so rewarding, and it can mature your soul and your whole being into another level. To be in front of an audience, whether it's five or 25, it doesn't matter. You have to be at the peak of your artistic career at 8 o'clock at night. It can be devastating sometimes, because the audience doesn't care if your mother died or your boyfriend broke up with you; they just want to see something amazing. I did it for 12 years every night, or double if it was matinees. But it gives you the tools to be an actor. If you just become an actor for TV or movies, it can be rewarding money-wise, but soul-wise, it's not. BSW