When Shakespeare famously wrote that, "All the world is a stage...", he was, of course, referring to the theatre. But ask virtually any one of today's actors, and they'll tell you that a big chunk of the world is now actually a sound stage on a studio lot somewhere. But no matter if you're acting for the theatre or acting for the camera (or both), an essential element is training. Experience, as we know, is probably the greatest teacher of all. But a college or university program has much to offer as well, as do other options such as a performing arts school, private study, class work with an established teacher, or classes in a specific physical element, such as voice, movement, or dance, or a technical element, such as camera technique. Ross Reports talked to three notable working actors about the kinds of training they received and how it has supported their work. Coincidentally (or not), they all have solid stage backgrounds with an emphasis on classical work, and they all enjoy film and television careers as well.

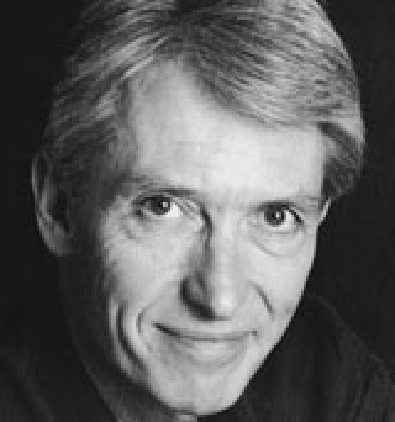

Mark Bramhall

Mark Bramhall has appeared on stage at the Mark Taper Forum, American Conservatory Theatre, La Jolla Playhouse, Portland Center Stage, and the Colorado Shakespeare Festival. His many film and television credits include NYPD Blue, 7th Heaven, That 70's Show, Introducing Dorothy Dandridge, Sliver and Vanilla Sky. Most recently, he was seen in the recurring role of Lazarey on ABC's hip spy series, Alias.

Like many actors, Mark Bramhall's beginnings were humble -- he played the March wind in a grade school play. But that began to change in high school. On the advice of an English teacher, Bramhall did part of Mark Anthony's speech from Julius Caesar to meet a school public speaking requirement. The response was encouraging, and the following year, the same teacher directed a production Twelfth Night and cast him as Malvolio. "Then I was hooked forever," he recalls.

After high school, Bramhall enjoyed a prestigious higher education. His four years at Harvard were marked by being president of the Harvard Dramatic Society, and appearing in approximately 60 shows in various venues. After graduation in 1965, he attended UC Berkeley as a grad student. The following year he traveled to the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Arts on a Fulbright Scholarship. Halfway through his first year, he was offered a position at the American Conservatory Theatre, in San Francisco, "with a salary and everything." He immediately accepted, and returned to California. "In those days," he recalls, "ACT was a full conservatory program. It was one of the nicest things that ever happened to me."

Bramhall believes a performance-rich schedule is a critical supplement to an actor's educational training. "The huge paradox about drama schools is that people are encouraged to think about everything they're doing," he says. "And that's death to a performance. You need a heightened state of awareness that's quite inaccessible by pathways of thought and is reached by pathways of instinct. So there's a huge amount of left-brain curriculum aimed at fostering a lot of right-brain activity. And a student actor has to grasp that, either through a train wreck that they realize came from over-thinking, or just because, when it's presented to them, they then understand about letting go."

The discipline of Bramhall's classical training has also supported him in his film and television work. Although he's always well-prepared on set, the trick, he says, is to then let go of all that. "When Michael Caine talks about acting for the camera, he speaks of being careful to never rehearse 100% so that you have something left to give," he explains. "But for classical stage, you need to go beyond what is acceptable just so you can find out where that mark is. That might happen in front of the camera, too, but it needs to be a surprise, both to you and to the people behind the camera. In classical stage work, you organize it more; you lay more foundations for it and aim more consciously at it."

Even with his background, Bramhall still takes class whenever possible. Currently he studies film and television technique with a teacher who encourages this state of "choiceless awareness." The actor credits many of his recent bookings to what he's learned in class.

And part of what he's learned, just through years of experience, is that show business is fraught with paradoxes. "It's difficult, in film and television, to have that state of real reckless abandon when you work. When I go into a stage audition, or when I'm performing on stage, I can get there easily. But it's much more difficult for me to do that in front of a camera. I have a whole lot of stuff on my resume, but it probably adds up to 5-6 hours in front of an actually rolling camera. My stage experience, however, is countless. It's just that much harder in film and television to acquire time where you really learn. You can do exercises, and go to hours of camera classes, but getting out there and working with the crew and meeting all the demands of shooting, and getting that feeling into your body and soul, that's precious. It's the doing of it -- in front of an audience, in front of the crew, in front of a rolling camera -- where you finally make the leap or not. And if you don't make the leap, then you learn something from that too."

Harry Groener

Harry Groener won a 1980 Theatre World Award for his debut Broadway performance as the nimble-footed Will Parker in the 1979 revival of Oklahoma!, for which he also received the first of three Tony Award nominations. Other nominations came for his roles as Munkustrap in Cats (1983) and as Bobby Child in Crazy for You (1992). Television audiences know him as the nerdy Ralph in Dear John, and as the evil mayor of Sunnydale, Richard Wilkins III, in Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Recent film credits include Amistad, Patch Adams, Road to Perdition, and About Schmidt.

Originally, Harry Groener wanted to be a dancer. He took ballet classes in San Francisco from ages 12 to 15, and then moved on to theatre when he hit high school. From 1970-76, he spent his summers with the Pacific Conservatory of Performing Arts in Santa Maria, CA, a well-known summer rep company offering a rotation of two musicals and three plays. It was here that Groener received his first serious training in the performing arts, working as an actor, dancer and choreographer. During the regular school term he attended City College in San Francisco. Then, in 1973, he enrolled in the actor training program at the University of Washington, which focused on classical works. He graduated in 1976.

"I got a lot of wonderful roles that I was too young for," Groener says of his time at U of W, "but the challenges were still there. You still developed a working process. But a lot of my standards toward theatre were shaped at PCPA. The training there was invaluable because you're not in classes, you're just doing the shows. You'd watch the older, Equity actors playing the leads, seeing how they worked, what their process was, the little things they did, and then you'd take that back to school with you. When you were cast in shows, you'd try to imitate the actors you saw during the summer, and eventually you would get the 'Aha!' experience, where you would go, "Oh, I see what they were doing!" Then it would become your own because now you understood it and you were no longer imitating."

Groener recommends the same look-and-learn technique when transitioning to auditions and acting for the camera. "Do your homework," he stresses. "Watch TV and films and see how they do what they do. Try to understand a facial expression at a particular camera angle, from far away or close up, and what the actor does. That's one of the things I think is lacking in theatre training; many schools don't teach you any of that stuff. And it's going to be at least an equal, if not a larger, part of your work when you get out there as an actor."

Deborah Strang

Deborah Strang has played on stage at Trinity Rep, Indiana Rep, Cincinnati Playhouse, and The Roundabout Theatre in New York. Film credits include Things to Do in Denver When You're Dead and Kiss the Girls. On television, she played Susanne Madison on Port Charles, and has been seen on numerous episodics, including ER, Touched by an Angel, The X-Files, Family Law and, most recently, HBO's Carnivale.

It's a case of small town girl makes good in the big city. Deborah Strang was born and raised in Big Stone Gap, Virginia, in the Appalachian Mountains. She performed in outdoor summer productions and the annual school play. Later, she attended Emory and Henry, a small liberal arts college near Abington. And despite her intentions of pursuing social work, she got involved in the drama department and graduated with an interdisciplinary degree covering English, music, speech, and drama.

By the time Strang reached grad school at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, social work was forgotten and she entered the school's Master of Fine Arts Program in theatre. After graduation, she moved to Boston and got her Equity card. Four years later, it was on to New York. She spent a decade there doing theatre and film work before relocating to Los Angeles in 1990, where she has since added an impressive list of television credits to her resume.

Strang acknowledges that her theatre training has helped her succeed on the screen as well. In this venue, she tends to get cast in roles she refers to as "dramatic crazies." A perfect example, she says, is the "Aubrey" episode of The X-Files, in which she played a congenial police inspector transformed into her murderous father.

"When I got that call, I thought, 'There's no way I'm going to get this!'" she laughs. "It was actually for a much younger woman than I am. And they only gave you sides, so I didn't know that I turned out to be the murderer. But I did have this one psychotic thing, so I could go in and be the normal person and then, in the next scene, be this other entity, turning into a man. It could have been much more difficult for someone who doesn't have the kind of training I do. At the same time, when I audition for a 'normal' woman who doesn't have those twists and turns, I don't usually get those roles."

Clarity of purpose is another aspect of training that's often overlooked. It's hard to get anywhere if you don't know what you want or where you want to go with your career. "Ask yourself, what do you really want in your life? If you're young and beautiful and want to do film and television, then get an agent right now. Go to LA or New York and go for it. If you want a life in musical comedy, you need voice, dance, and some endurance training as an actor. Certainly if you want to do classical theatre you must have training -- voice work, text work, etc. But if you're a character actor, you've got some time. You might get cast in a few things when you're young, but unless you're really specific -- strange-looking or obese or something really extreme as a character person -- chances are that you won't really have a career until you're older, so you have time now to build up some training and get a little experience. Do regional theatre! Experience is a great confidence builder."

To learn camera work, Strang was helped by classes in commercial technique. But she stresses that her biggest training for that medium was experience. While in New York she won the lead in a film that took five years to complete. "The people were wonderful and crazy and they kept running out of money," she remembers. "We all got very involved and did everything -- camera work, continuity, watching the rushes, lines, blocking. All elements of it became ours. And I got very accustomed to being in front of a camera and knowing what the camera was capable of.

"But experience isn't the whole story. With just experience, you can get into ruts and turn into a hack. And that's where occasionally it helps to go back for coaching or more training, or to take classes in other areas of production, of life. One of the greatest benefits to any actor is to be a person alive in the world. If you do nothing but training day in and day out, it becomes very intellectual and myopic. Being a whole person onstage means whole person in life."